玉川田園調布 世田谷区 東京都

Tamagawa Denen Chofu, Setagaya, Tokyo

Spring/Summer, 2020

Tamagawa Denen Chofu, Setagaya, Tokyo

Spring/Summer, 2020

長引くパンデミックと、繰り返される外出自粛要請により、プロジェクトの準備期間も延びました。コロナウイルスに関わる事態の変化と共に、作品のデザインの方向性は、幾度となく転換を余儀なくされました。目に見えない脅威と戦うということは、東日本大震災をテーマに取り扱うプロジェクトとして、元から念頭に置いてきたことです。コロナ禍での生活だからこそ、どうすれば安全に人を巻き込み、人と交流することができるかを考え直す必要がありました。

The prolonged pandemic and cyclical shutdowns allowed us time for much-needed additional research. Our design concepts pivoted and morphed as we continued to learn about COVID-19. Contending with invisible risk in relation to the 311 Triple Disaster has been a project theme from the start. Living with the corona virus, we have been forced to reinvent ways for communities to safely engage and interact.

The prolonged pandemic and cyclical shutdowns allowed us time for much-needed additional research. Our design concepts pivoted and morphed as we continued to learn about COVID-19. Contending with invisible risk in relation to the 311 Triple Disaster has been a project theme from the start. Living with the corona virus, we have been forced to reinvent ways for communities to safely engage and interact.

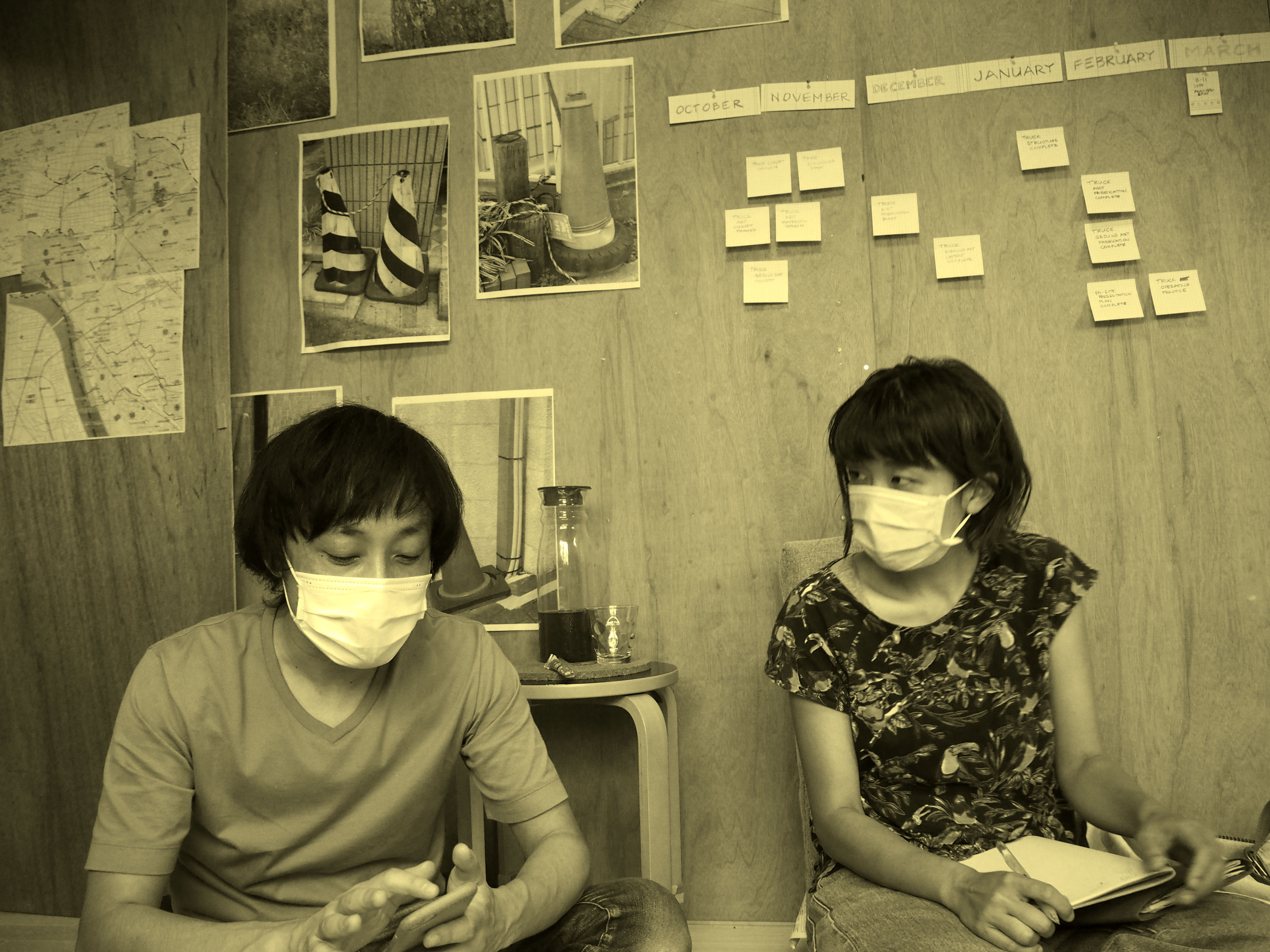

2020年春の緊急事態宣言発令後すぐ、必要に駆られて自宅アパートの一部を作業場に改装しました。木造の「部屋の中の部屋」として誕生した作業場は、思いついたことを言葉にできる話し合いの場になりました。「旅はすみか」をどう形作るかについて、再検討を重ね、状況に適応してきた過程を可視化したのです。

週ごと月ごとのパンデミックの状況変化によって、制作計画の練り直しを強いられました。当初の計画では、荷台部分を集いの場に改造した2トントラックに乗って、東京から福島まで旅をする予定でした。実際に東日本大震災を体験した方々を少人数のワークショップをお招きし、とてつもない大災害をどうすれば乗り越えられるのかについて、直にお話を伺いたかったのです。江戸時代前期の俳諧師松尾芭蕉の作風から学び、体験者の生の声から、新しい形の俳句を一緒に編み出していこうと考えていました。

ですが、コロナ情勢下では、遠距離の旅行や対面で集うことが感染を拡大させかねないとわかった時点で計画を変更しました。今度は、被災地から送ってもらう資材を使って、風力で音を奏でる楽器にトラックを改造できないかと考えました。砂時計型のしかけは、和楽器の鼓を模し、コロナ禍で歪んだ時間の感覚を表します。ところが、被災地から資材を調達することは論理的に不可能でした。さらに、公共の場に不特定多数の人々を集めて行う企画に伴うリスクは、回避すべきと判断したのです。

数々の方向修正を行いましたが、私たちのプロジェクトの第一目標は何よりも大切にしようという意志は貫いてきました。その目標とは、東北地方の人々の聞かれざる声を、より多くの人へ届けようということです。

Early in the spring state of emergency, we coverted part of our flat into a much-needed workspace. This wooden ‘room-inside-of-a-room’ became a meeting space where we could think aloud. We made visible the many permutations and adaptations of Tabi Wa Sumika’s form.

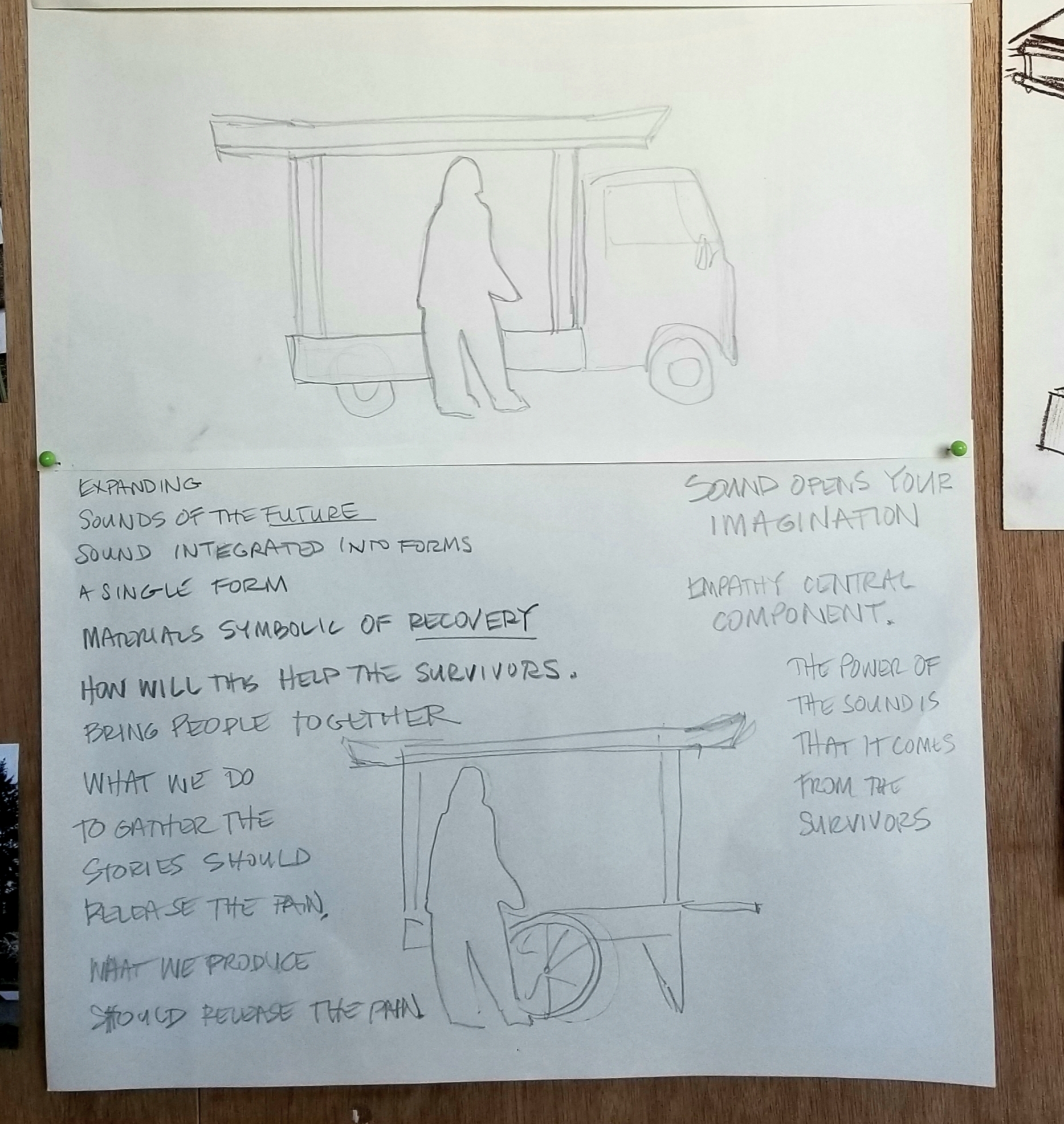

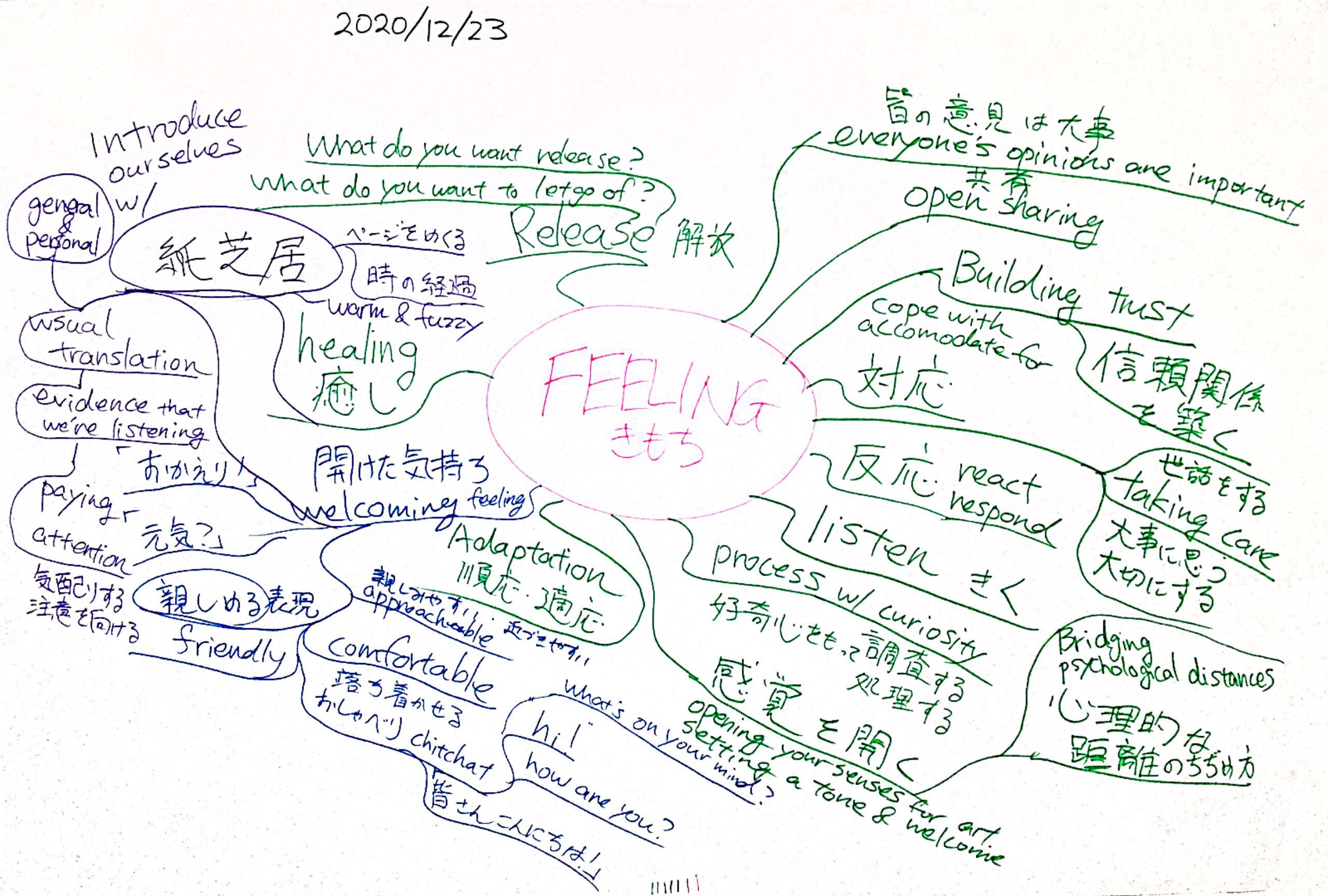

Week by week, month by month, the pandemic’s influences compelled us to change our creative strategies. We had initially planned to travel from Tokyo to Fukushima in a 2-ton truck outfitted with an artists’-designed gathering space. We wanted to meet with survivors in small groups, to learn from their strategies to overcome a monumental disaster. From their expressions, we planned to generate a new form of collaborative haiku based on the ethos of Matsuo Basho, the 17th century originator of contemporary haiku.

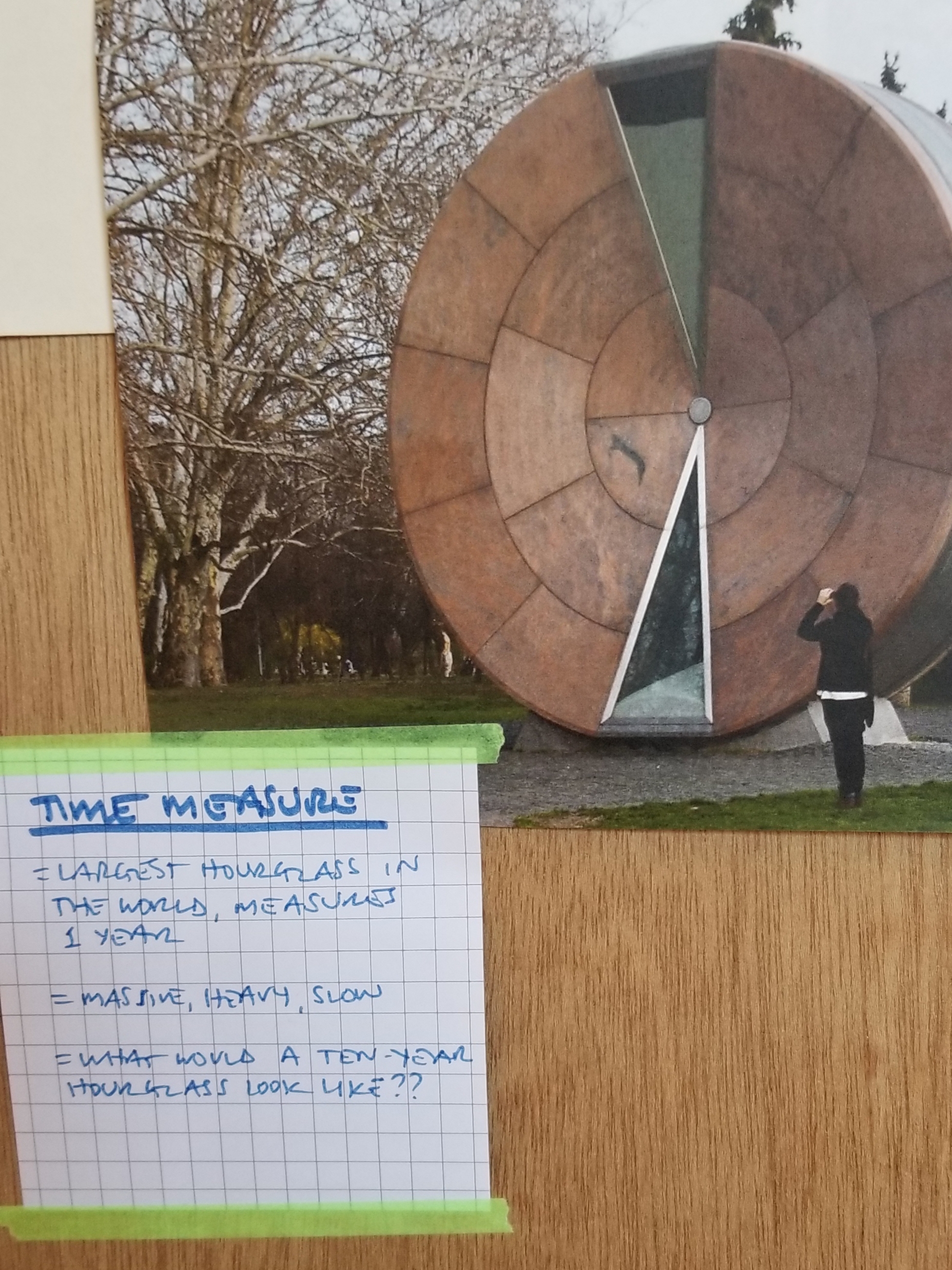

When it became clear that it was no longer safe to travel or meet in groups, we imagined how this truck could become an instrument to be played by the wind using materials from the disaster-region. Hourglass forms referenced traditional drums, and spoke of the strange passage of time. But was logistically impossible to obtain these materials. And staging any type of public interaction at all posed risks that we were not willing to take.

Throughout these changes, we were determined to stay true to our primary goal: highlighting unheard voices from the Tohoku region.

週ごと月ごとのパンデミックの状況変化によって、制作計画の練り直しを強いられました。当初の計画では、荷台部分を集いの場に改造した2トントラックに乗って、東京から福島まで旅をする予定でした。実際に東日本大震災を体験した方々を少人数のワークショップをお招きし、とてつもない大災害をどうすれば乗り越えられるのかについて、直にお話を伺いたかったのです。江戸時代前期の俳諧師松尾芭蕉の作風から学び、体験者の生の声から、新しい形の俳句を一緒に編み出していこうと考えていました。

ですが、コロナ情勢下では、遠距離の旅行や対面で集うことが感染を拡大させかねないとわかった時点で計画を変更しました。今度は、被災地から送ってもらう資材を使って、風力で音を奏でる楽器にトラックを改造できないかと考えました。砂時計型のしかけは、和楽器の鼓を模し、コロナ禍で歪んだ時間の感覚を表します。ところが、被災地から資材を調達することは論理的に不可能でした。さらに、公共の場に不特定多数の人々を集めて行う企画に伴うリスクは、回避すべきと判断したのです。

数々の方向修正を行いましたが、私たちのプロジェクトの第一目標は何よりも大切にしようという意志は貫いてきました。その目標とは、東北地方の人々の聞かれざる声を、より多くの人へ届けようということです。

Early in the spring state of emergency, we coverted part of our flat into a much-needed workspace. This wooden ‘room-inside-of-a-room’ became a meeting space where we could think aloud. We made visible the many permutations and adaptations of Tabi Wa Sumika’s form.

Week by week, month by month, the pandemic’s influences compelled us to change our creative strategies. We had initially planned to travel from Tokyo to Fukushima in a 2-ton truck outfitted with an artists’-designed gathering space. We wanted to meet with survivors in small groups, to learn from their strategies to overcome a monumental disaster. From their expressions, we planned to generate a new form of collaborative haiku based on the ethos of Matsuo Basho, the 17th century originator of contemporary haiku.

When it became clear that it was no longer safe to travel or meet in groups, we imagined how this truck could become an instrument to be played by the wind using materials from the disaster-region. Hourglass forms referenced traditional drums, and spoke of the strange passage of time. But was logistically impossible to obtain these materials. And staging any type of public interaction at all posed risks that we were not willing to take.

Throughout these changes, we were determined to stay true to our primary goal: highlighting unheard voices from the Tohoku region.